Mining: An Unavoidable Reality for Achieving Climate and Technology Objectives

A new economic framework for the Western Hemisphere could secure critical minerals supply chains needed for clean and advanced technology — while keeping sustainable mining practices top of mind.

Photo Credit: iStock, zetter

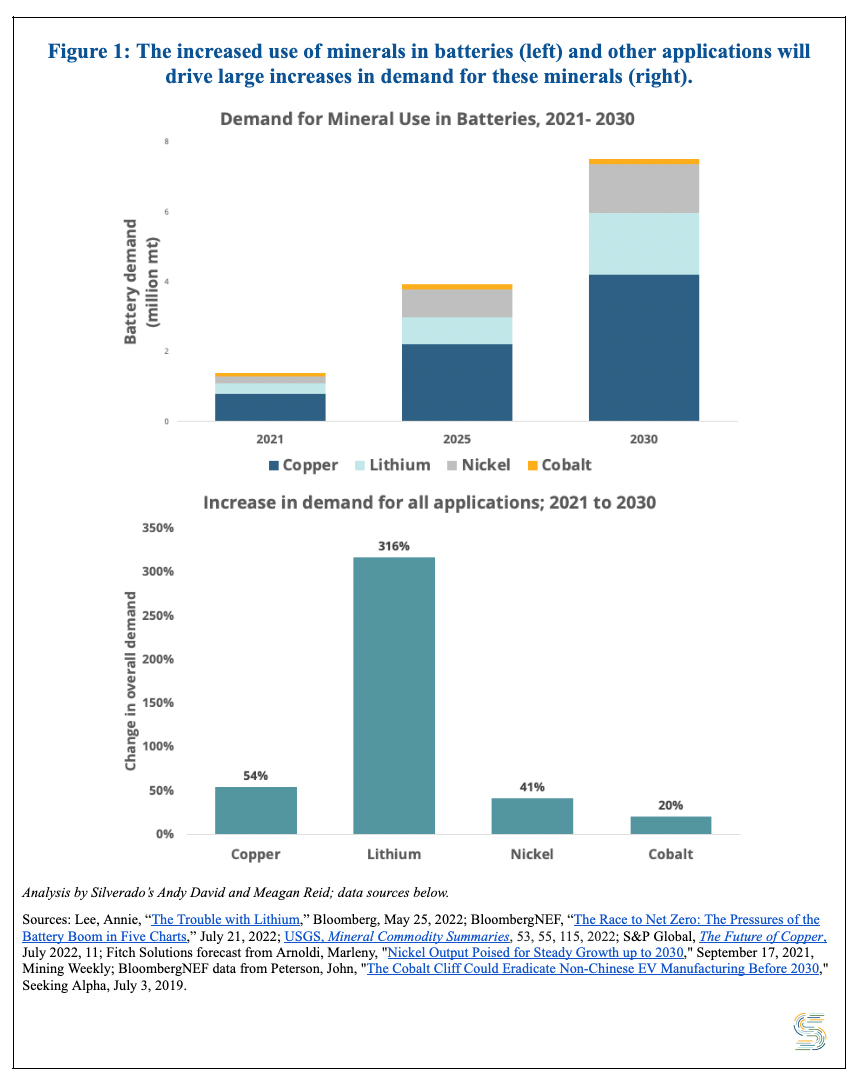

Combating climate change and increasing mineral extraction are not often thought of as compatible goals. Yet growing evidence suggests that in order to meet skyrocketing demand for the environmental technologies that will support the clean energy transition (e.g., wind, solar, energy storage, geothermal power), countries including the United States will need to dramatically increase their supply of the critical minerals - lithium, cobalt, and rare earths - that form the foundations of these technologies. By some estimates, achieving the Paris Climate Agreement’s baseline goal of stabilizing global temperature rise below 2°C requires quadrupling mineral development for clean energy technologies by 2040. Achieving the even more ambitious goal of a net-zero world by 2050, meanwhile, likely requires a six-fold increase in critical mineral supply.

To further complicate the matter, the mining and production of these critical minerals remains highly concentrated in a small number of countries. For example, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Russia together supply roughly 54% of the world’s nickel, while the Democratic Republic of Congo supplies approximately 70% of world cobalt mine production. Moreover, the United States’ main economic competitor — China — has already made extensive investments in the mining operations in these regions, giving the PRC disproportionate power over the rest of the world for critical mineral supply.

From an environmental perspective, then, the question is not if but how the United States and its allies should expand their access to critical minerals to meet the twin objectives of supporting the clean energy transition while reducing reliance on China’s growing influence in this sector. At the same time, however, increasing mining and processing to meet the demand of the clean energy transition must be done with regard for workers’ rights, environmental protection, and the economic and political interests of the countries and communities that produce these minerals. If properly executed, this approach can also spur economic growth and investment in local communities, and support R&D for more sustainable mining practices.

The new Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity (APEP), unveiled by President Biden at the June 2022 Summit of the Americas, is one such catalyst for this approach. Across the board, APEP seeks to drive economic recovery and growth in the Western Hemisphere, with a focus on building more resilient supply chains and supporting climate goals. The APEP could leverage the extensive network of regional trade and investment deals to propel initiatives for the secure and resilient critical mineral supplies of the future.

With demand set to grow across major metals and minerals over the coming decade, the battle over natural resources will become more acute (figure 1). Because of that, a visionary and committed APEP should immediately prioritize an action plan that attracts investment, deepens regional partnerships and trade ties, diversifies Latin American export markets, and supports a sustainable regional mining framework.

Prioritizing Critical Minerals for Early Action

To start, the United States and APEP partners, once initially identified, should target critical minerals that are geographically concentrated in the Western Hemisphere and for which new or expanded mining and processing capacity would help support the advancement of key APEP goals like cutting carbon emissions through the further production and deployment of clean technologies.

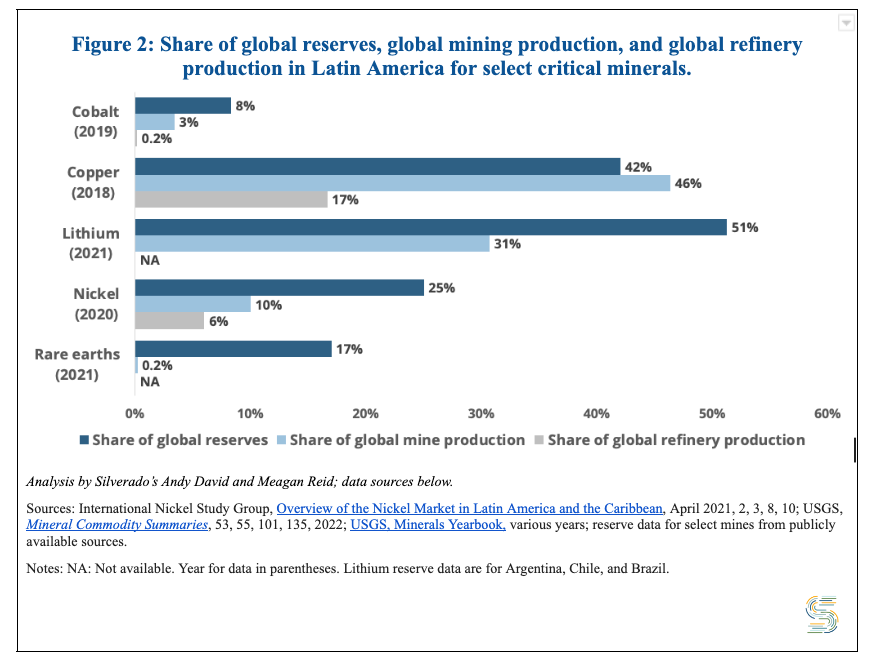

As shown in Figure 2, while Latin America is rich in reserves, and moderately positioned in terms of production, it lags in value-add mineral refining. This fact pattern supports exploration of new opportunities for the U.S. and APEP partners to work together to build a more globally competitive regional market for these minerals and the technologies that require them.

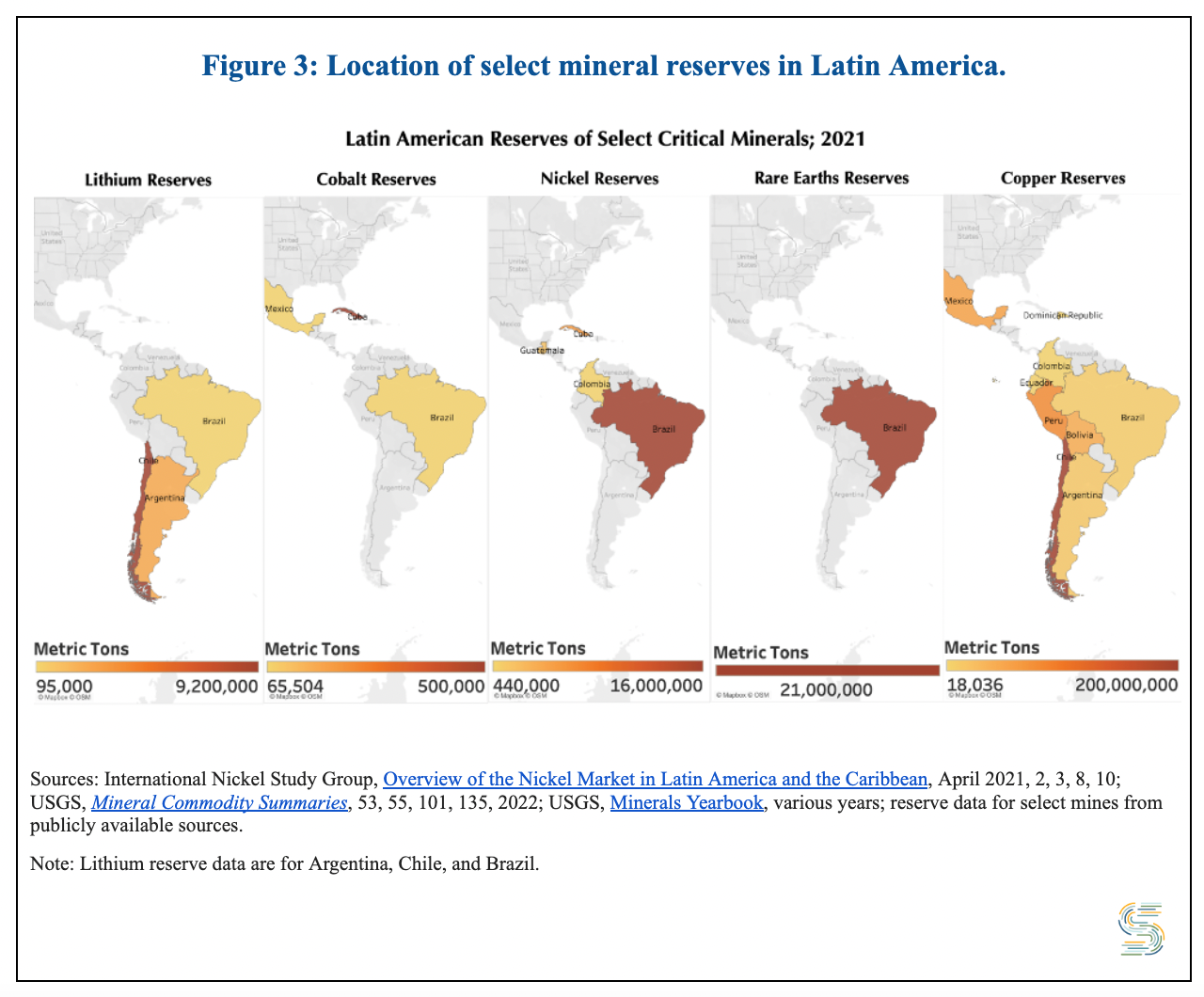

Looking at where these minerals are dispersed across the region is also instructive in identifying potential APEP leading partners - albeit a whole of region approach will be necessary.

For lithium, Argentina, Bolivia and Chile are likely candidates for exploring deepened partnerships, a key input for batteries for electric vehicles. Chile, in particular, is the world’s second largest lithium producer, reporting a nearly $1 billion lithium trade surplus in 2021. Despite the low tariffs among many partners in the region, no other South American countries were present in Chile’s top three export destinations (which are China, South Korea, and Japan). The APEP could launch a working group specifically focused on the unique challenges and opportunities in lithium mining and processing that both addresses surrounding community and environmental impacts while also exploring project development and investment opportunities that support an equitable distribution of local economic and environmental benefits.

Copper reserves are also abundant, especially in Chile where it has previously been estimated that $150 billion in investment is needed to double copper output by 2050. With global copper demand set to increase more than 50% by 2040, driven in part by the increasing demands for solar, wind, and energy storage, the APEP could lead work on identifying the regulatory and trade structures needed to scale copper production and realign markets to meet this demand.

Additionally, rare earth elements are significantly underdeveloped in terms of production and refinement. For example, Brazil has 17 percent of global rare earth reserves, and although there have been some recently announced investments, there is much potential for growth. Cobalt, which is commonly recovered as a byproduct of copper and nickel mining, also has growth potential. APEP could promote sustainable extraction and processing and refining capacity expansion that lead to economic development and job creation.

APEP as a Catalyst for Change: Recommendations

To build critical mineral supply chain resiliency and incentivize socially and environmentally responsible production, APEP should:

- Prioritize critical minerals supply resiliency to meet the agreement’s primary goals of creating clean energy jobs, mobilizing investment, advancing decarbonization, and ensuring sustainable trade. To assess the feasibility of developing a regional supply chain, APEP partners should:

- Evaluate current supply and demand and the opportunities and challenges to creating a balance, including by anticipating potential supply crunches and early warning systems to help prevent and mitigate market disruptions;

- Survey current investments in regional mining and processing projects and identify gaps where future investment is needed and sources for that investment, be they public, private, or through the banking system;

- Consider the extent to which additional infrastructure plans are needed to support mining or processing expansion;

- Evaluate existing laws and regulations for mining and production activities, including provisions for environmental protection, worker safety and community health to ensure there is a framework for sustainable future action;

- Explore ways to diversify processing and refining away from single sources outside of the region;

- Develop specific sub-action plans for each critical mineral (e.g., the strategy for lithium will be different than for rare earths, as noted above);

- Analyze the projected impacts for jobs, economic growth, and emissions in the region from increased partnership and investment in critical minerals supply chains; and

- Design robust stakeholder engagement with businesses and local communities.

- Foster cooperation that establishes a complete “mine-to-market” critical minerals supply chain, starting with a full study of existing critical mineral industries to identify gaps in infrastructure requirements, skills development needs, policies and regulations needed to spur action, and to discover how the circular economy could also play a role. The study would catalog critical mineral reserves as described above along with information about current and potential refining and production capacity close to source and/or in neighboring countries.

- Leverage existing frameworks, starting with U.S. free trade agreement (FTA) and Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) partners that already share a common vision for economic opportunity and trade liberalization. For example, FTAs provide a range of opportunities and platforms at ministerial, senior official, and technical expert levels for partners to convene on cross cutting issues such as supply chain resiliency and to further the work of the APEP. Similarly, the U.S. and Canada already have a Joint Action Plan for Critical Minerals under the Roadmap for a Renewed U.S.-Canada Partnership that could be further leveraged to advance APEP’s goals. In addition to collaboration through the Joint Action Plan, the U.S. and Canada are founding partners in the Energy Resource Governance Initiative where they focus on mining sector stewardship to mitigate risks to local communities, workers, and the environment. Initiatives like these contribute to the development of higher value-add critical mineral industries to meet exploding supply demands for batteries for zero-emissions vehicles and renewable energy storage. If APEP were to augment these efforts, it could set the precedent for responsible mining and sourcing around the world.

- Link APEP with the Minerals Security Partnership. The Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) already focuses on ensuring that critical minerals are “produced, processed, and recycled in a manner that supports the ability of countries to realize the full economic development benefit of their geological endowments,” specifically by facilitating government and private sector investments in critical mineral supply chains. The current MSP membership does not appear to include countries in Latin America, but moving forward, APEP could facilitate discussions that move the MSP towards integrating APEP partners that could shape the investment incentives for their critical mineral mining and processing expansion.

- Seek stakeholder input and develop principles to guide critical minerals partnership. Within APEP, these principles should include a focus on transparency, ethics, and sustainability and promote collaboration among governments, business and civil society. These networks will inform APEP’s work and should begin with a formal consultative process through a published Request for Information and continue with regular outreach throughout the region.

Conclusion

APEP’s creation comes at an opportune time to deepen partnerships between like-minded countries and trading partners, the private sector, and local communities. By focusing on critical minerals as an early action item, it can mitigate supply chain challenges, grow climate-related industries, bring climate solutions to local communities, and put the region in a globally competitive position in this sector with far reaching benefits for economic and national security.

Sarah Stewart is Silverado Policy Accelerator's Executive Director. Adina Renee Adler is the Deputy Executive Director. Haley Ryan is a Policy Analyst.

Pillar

Trade and Industrial Security