International Considerations for a Net-Zero Trade Policy

What would a positive agenda for an international, net-zero trade policy look like?

Photo: Annie Spratt

With a new year ahead of us, it’s time for a fresh look at how international actions can help mitigate the climate crisis.

The final months of 2021 saw a flurry of international action around climate change. In November, parties to the United Nations’ Climate Change Conference convened in Glasgow and agreed on a range of plans designed to limit the rise of global temperatures above to 1.5 degrees. Among the plans were agreements to hasten the global transition away from fossil fuels, reduce methane emissions, and reverse deforestation. With these agreements now on the books, all eyes have turned to the implementation of these policies at the nation level, as international observers wait to see whether individual governments can operationalize their agreements in spite of domestic and international political challenges, widespread energy crises, and wavering domestic ambitions.

In mid-December, after postponing its ministerial conference due to coronavirus concerns, the World Trade Organization formally launched plurilateral ministerial declarations on three environmental initiatives: trade and environmental sustainability, plastics trade, and fossil fuels subsidies reform. While these initiatives are a welcome development, WTO member nations still have a long way to go to define trade’s role in addressing the climate crisis and setting a serious work program aimed at creating a net-zero future. Fresh off COP26, these challenges must be top-of-mind for the U.S. and it's like-minded trading partners in the WTO.

As the agreements that emerged from COP26 and WTO made clear, large multilateral agreements based on voluntary commitments can help mobilize international ambition towards a net-zero future. But these agreements also present challenges. For one, they take a significant amount of time and resources to implement, limiting their usefulness for addressing near-term concerns. Second, these agreements are in many cases not designed to hold parties accountable when they fail to meet their commitments. Given these constraints and the urgency of the climate crisis, the United States must consider the full range of complementary trade tools at its disposal in addition to these these agreements to prompt its trading partners to reduce their emissions, expedite the uptake of innovative environmental technology, transition to cleaner energy sources, and adopt stronger environmental compliance and oversight measures.

To maximize trade policy’s overall utility in combating the climate crisis, the U.S. will have to work directly with its trading partners both inside and outside of the WTO to create international trade frameworks and agreements that prioritize improved environmental outcomes and lower carbon emissions. One important trade tool that can be effective in this effort—if used strategically and in concert with other tools including foreign aid and technical assistance—is a carbon border adjustment mechanism, or CBAM.

Yet even as the U.S. considers a domestic CBAM option, it will need to decide on a positive international agenda that lays out its strategy and objectives for carbon adjustment across all levels of the international trade landscape. Here’s what the foundation of that agenda could look like:

1. Approaches: Multilateral, Plurilateral, Regional, Bilateral, Unilateral?

The ultimate goal of a net zero trade policy is to achieve a multilateral arrangement for border adjustment that can render distinct national systems interoperable and that guarantee transparency, fairness, and efficiency for governments and businesses alike. Yet, unfortunately, it is unlikely that such a multilateral arrangement is achievable in the near term. If the past is prologue, the U.S. can reasonably anticipate a twenty-year arc of negotiations—at minimum—before a global carbon trading system comes to fruition. The climate, however, does not have until 2042 for governments to start controlling carbon emissions at the border, meaning that interim arrangements among like-minded nations will be necessary as stepping stones toward a broader carbon-progressive trade agenda.

Despite the challenges of achieving a multilateral agreement and the necessity of short-term actions, policymakers should understand that a multilateral agreement remains their ultimate goal and work to identify and/or create forums that can facilitate technical discussions in support of interim bilateral and regional agreements between trade partners. In the short-term, policymakers' should also move ahead with intuitive bilateral, regional, and even plurilateral options while simultaneously evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of potential forums and combinations of forums.

The greatest risk to the development of a successful carbon trading system—and, by extension, to the global economy—will likely come from uncoordinated unilateral approaches toward border adjustment. Unilateral moves lower the likelihood of successful international integration of border carbon policies since they focus primarily on national defensive interests and may not contribute to the environment for workshopping and problem solving that is necessary for negotiated outcomes between countries. Furthermore, unilateral options carry a substantial risk of facilitating carbon arbitrage and intentional down-stream offshoring of industries in order to circumvent carbon taxes.

Finally, the international community is likely to view unilaterally-imposed border measures as unhelpful or illegal, and they may spur retaliatory unilateral measures and a spate of new litigation in the WTO or within the trade adjudication processes afforded for in regional trade agreements. Resolving the challenges inherent in CBA policies through trade litigation can be time consuming, costly, and likely lowers ambition to adequately address carbon leakage at the border. These risks can be mitigated to some extent, although not eliminated, by designing measures transparently and in a non-discriminatory and not overly restrictive manner.

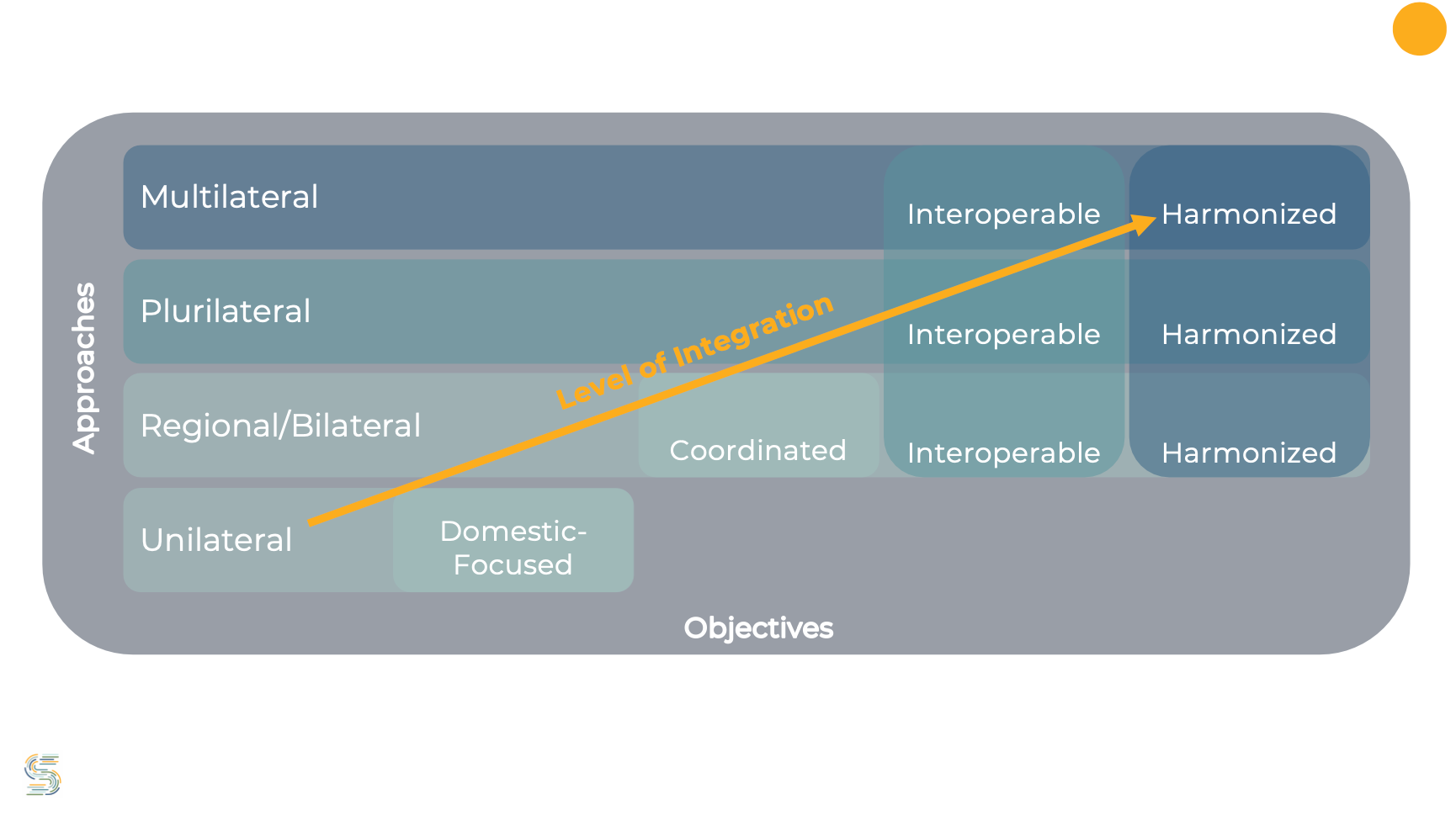

Figure 1. Approaches and Objectives for Carbon Border Adjustment

2. Objectives: Harmonization, Interoperability, Coordinated, or Domestic-Focused?

In concert with ongoing discussions about the proper approach, the U.S. needs to establish its objectives for international CBA policies. The objectives of international systems (or non-systems in the case of unilateral approaches) fall into four descending categories by level of integration: harmonization, interoperability, coordination, and domestic-focused (see figure 1).

Domestic-focused objectives correspond to a unilateral approach rather than the negotiated outcomes that result from regional/bilateral, plurilateral, and multilateral approaches. Unilateral/domestic-focused models benefit from expediency, since they focus on attributing full benefits to American workers and industry and can easily defer to existing U.S. methods for accounting and rule-making. While a unilateral approach that prioritizes domestic interests could be a useful starting point, autarky over the long term tends to carry more costs for the economy than benefits. Those costs are likely to include higher costs paid by both importers and exporters, diminished export competitiveness, and fractious commercial relationships with allies and partners.

Coordinated regional approaches—including bilateral agreements—could serve as an interim step toward greater integration of systems while preserving the autonomy that domestically-focused unilateral systems would afford. A coordinated regional approach would see partner countries, such as the USMCA countries, implementing their own CBAs synchronously with the potential to forgo such measures at the Northern and Southern border. Such an approach would save North American manufacturing value chains substantial headaches and compliance costs.

Ultimately, the goal of WTO is to facilitate trade through interoperability, not necessarily through harmonization. Whether we start with regional or plurilateral groups, the goal should be interoperability with a harmonized border language—an analogous model to the relationship between the GATT and the WCO’s harmonized tariff system.

Given the dire need for climate action, the U.S. shouldn’t let the perfect—i.e. a fully harmonized system—be the enemy of the good—i.e. a sufficiently interoperable system. “Close enough”—meaning a system that can deal with environmental externalities and that is easy enough to implement without placing burden on international commerce—will suffice, and may even be a way to optimize international diversity and preserve national interests like the right to regulate.

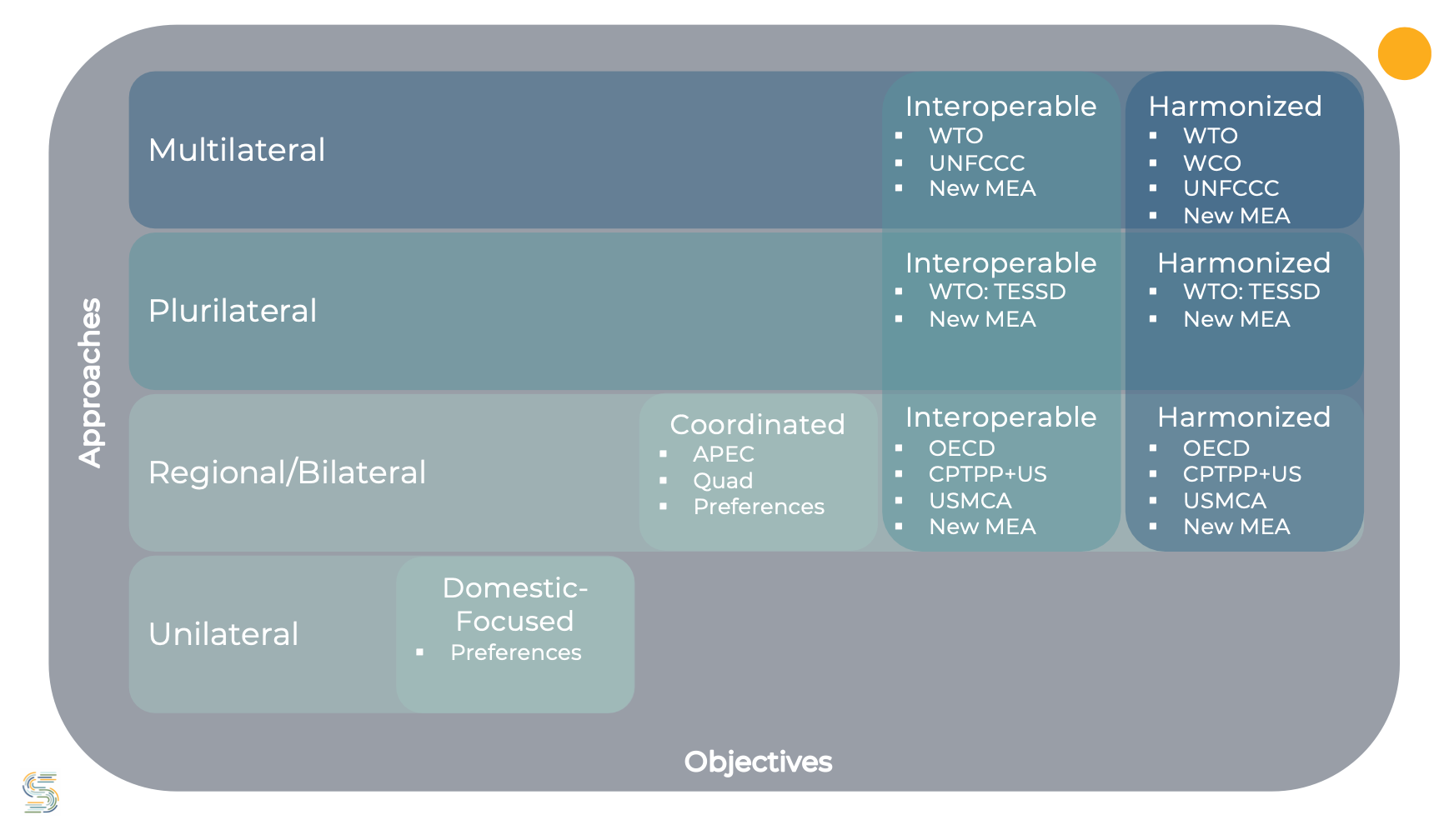

Figure 2. Potential Forums for Carbon Border Adjustment

3. Forum (s): WTO, UN, or something different entirely?

The final institutional question concerns which institutions are best suited to host negotiations on —and support the resulting operational frameworks for—a regional and eventually global carbon adjustment system. The challenge with institutional choice is that a successful outcome will require a functional merger of trade policy and carbon accounting disciplines. Forums to consider include:

The World Trade Organization

The WTO’s technical expertise and negotiating experience, as well as lessons learned over 70-plus years of negotiation, make it the intuitive forum for addressing net zero trade policy. The Geneva-based organization benefits from its well-established institutional ability to implement border measures, square national systems with the interests of international commerce, and (at least nominally) provide a legal mechanism for the adjudication of disputes. The current work being done in the WTO’s trade and environmental sustainability structured discussions (TESSD) and Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE) could provide a springboard for such negotiations.

However, there are concerns as to whether carbon border adjustment mechanisms contradict the WTO’s core principles of national treatment and most favored nation treatment. Furthermore, the technical learning curve on determining a common framework for carbon accounting at the product level, assessing and verifying carbon tariffs fairly, establishing ‘rules of origin’ for said tariffs within global supply chains, and rescheduling duties on a regular basis based on national progress towards carbon neutrality are all formidable barriers.

The World Customs Organization

The WTO’s relationship with the World Customs Organization has been the backbone of the world trade system, enabling the creation of a bustling global economy. The WCO’s role in governing harmonized customs nomenclature—the harmonized language and science that identifies every tangible product on the planet so that trade can be fairly and transparently governed at the border—provides a common border language that allows customs agencies to operate.

Harmonization is achievable in large part because the WCO is a neutral, science-based organization. Its role has led to technical excellence in calculation and scientific evaluation and verification of products of every scope, skills that will most certainly be necessary to agree upon a common method for carbon calculation and identifying carbon intensity of products so that governments can schedule and negotiate border adjustments. These qualities make the WCO a strong candidate for inclusion in the carbon accounting decision-making process and border adjustment operations. Whether or not the WCO is part of the institutional framework that evolves, any regional or global carbon trading system will need an analog to it.

The UNFCCC

Another option is to move these negotiations to a climate-focused forum such as the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC benefits from a larger overall membership while possessing extensive technical expertise on the sources of carbon emissions. However, the UNFCCC would face fundamental challenges in advancing a trade-related agenda, since the forum has no trade or industrial negotiating expertise, is focused primarily on government commitments, and doesn’t have the kind of built-in mechanism that would allow it to integrate commercial and industrial stakeholder interests into the broader matrix of stakeholder input. Because of these shortcomings, there would be a great deal of economic risk associated with focusing negotiations within the UNFCCC. The economic and tariff inversion risks that could result from such a move could potentially create greater incentives for manufacturers to offshore larger parts of their value chains to pollution havens, resulting in catastrophic outcomes for global climate objectives and economic interests.

Another formidable challenge with the UNFCCC is its voluntary nature. Tariff commitments function best in bound settings, and it is hard to imagine governments agreeing to a voluntary, non-binding mechanism at the international level and a bound system at the national level. Nonetheless, the UNFCCC’s nationally-determined contributions will drive the policy decisions on how national governments choose to implement carbon elimination mechanisms and subsequently approach border measures, meaning that linkages to this critical institution will be necessary in any resulting global border adjustment institution.

A Native Trade-Related MEA

One approach to overcoming the challenges that arise from the attempt to integrate net zero trade policy into an existing trade or environmental forum could be the formation of a trade-related Multilateral Environmental Agreement (MEA). By creating a mission-specific institution that could provide a greenfield for the necessary marriage of trade and climate disciplines, this approach would carry clear benefits.

However, there are a number of risks associated with the creation of a native MEAN that would need to be taken into account. First, if a large number of major emitters are absent from the table, a MEA may suffer from questionable membership and effectiveness. There would also be a need to coordinate closely with other international organizations—including the WTO and the UNFCCC—in order to avoid a situation in which this organization contradicts or contravene’s other international obligations in commerce or carbon reduction. Tension already exists between the disciplines of the WTO and certain trade-related MEA’s of less substantial membership.

This leads to another fundamental risk of negotiating culture. Many international institutions prize a negotiating culture characterized by polite positional intransigence that lowers ambition and reduces attention to technical challenges. A successful net zero trade policy forum will need to be staffed by negotiators that are dedicated to being tough on the technical and political issues while sharing a mutual admiration for their shared problem solving goals. Similarly, a new organization could be vulnerable to staffing risks. For instance, if the staffing balance between trade and climate expertise is poorly distributed, a MEA could suffer from a lack of institutional memory, making it prone to repeating prior mistakes.

Regional Organizations (NATO, APEC, OECD, CPTP, etc.)

Regional strategic and economic organizations often incubate policy innovations. Recall, for instance, that GATT 1948 entered into force with just 23 contracting parties, while the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum has been incubating novel trade policies—many of which have percolated into regional and global disciplines—through its cooperative approach since the initiation of the Bogor Goals in 1994. Policy planners should therefore not underestimate the value of incubating regional approaches either concurrently with or prior to international efforts.

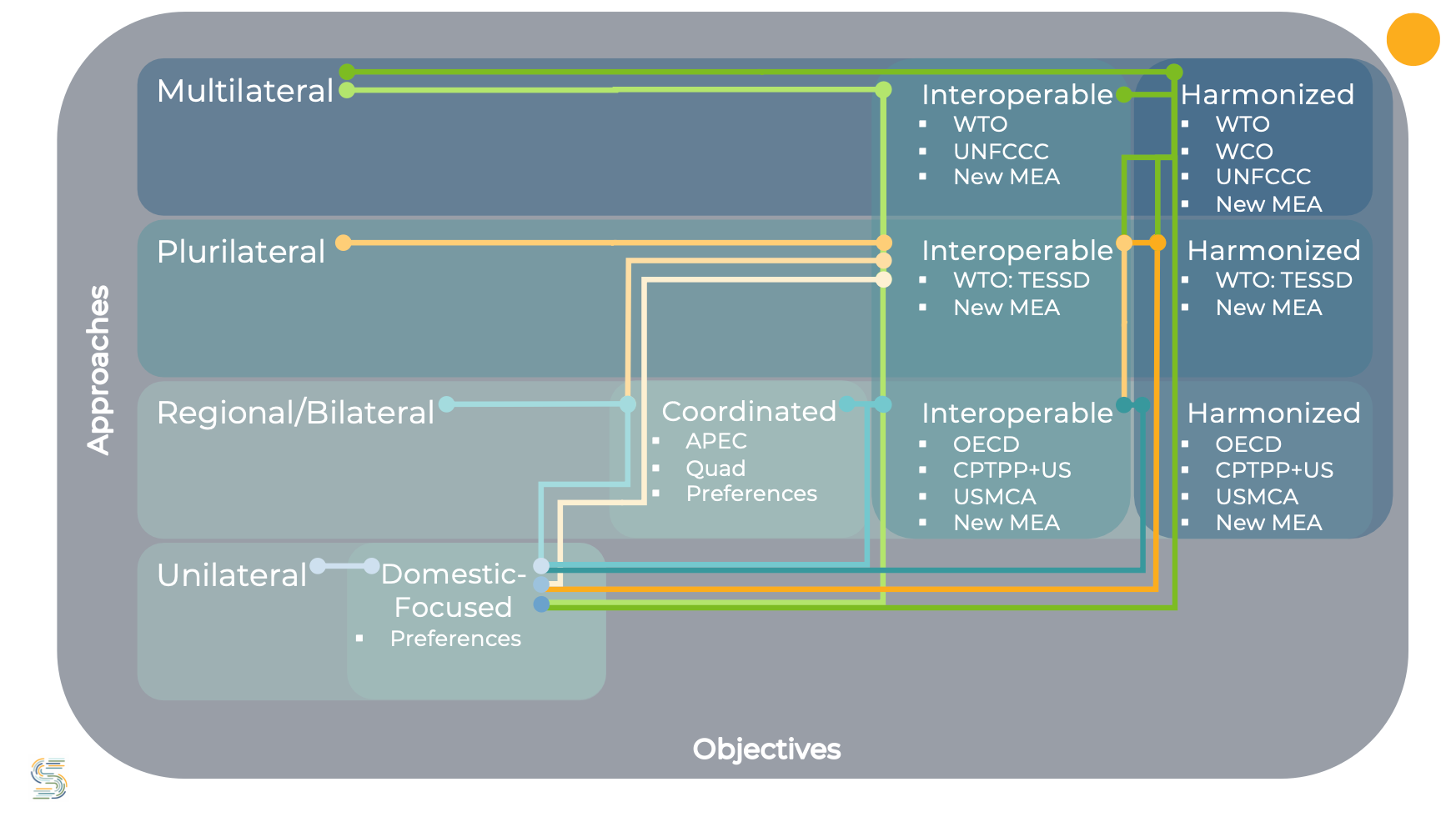

Figure 3. Potential Pathways to a Global Border Adjustment Mechanism

As Figure 3 demonstrates, the path toward an integrated international system is not dependent on a single starting point or concurrent exercises in lateral regional organizations. Serious consideration of border measures will require a careful evaluation on the part of the U.S. government as to the optimal pathways towards a global mechanism as we attempt to square our climate ambition with our economic interests.

Pillar

Eco²Sec