Critical minerals are defined in Section 7002 of the Energy Act of 2020 as any non-fuel mineral, element, substance, or material that has a high risk of supply chain disruption and serves an essential function in one or more energy products, or any mineral designated as a critical mineral by the Secretary of the Interior. The Energy Act of 2020 also specified criteria for developing an updated critical minerals list that accounts for supply chain risks. To date, the U.S. government has three separate critical minerals-related lists maintained by the Department of Defense, Department of Energy, and the Department of Interior’s U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) that are tailored to their agency’s respective missions. These lists offer invaluable data on U.S. import dependencies and source of imports; however, each may contain up to 50 critical minerals.

While existing critical mineral-related lists provide valuable technical insights, they are not crafted to guide policymakers to focus on minerals that pose the most immediate threats to U.S. economic and national security. Confusion persists in policy circles over which critical minerals are most vulnerable to supply chain disruption and require even further prioritization of executive and legislative action due to factors such as their centrality to defense use cases and lack of diversified sources. Crafting a whole-of-government approach to all critical minerals is challenging due to the intricacies of each critical mineral’s unique supply chain, pricing structures, and varying degrees of risk posed by import dependence on certain countries—particularly foreign entities of concern (FEOCs). To ensure accelerated action in an area of acute national security concern, an even more targeted list of “strategic defense critical minerals” is urgently needed. This list will enable policymakers to prioritize actions that create more resiliency for these minerals and diminish the outsized global influence of FEOCs, like China, in the critical minerals supply chain.

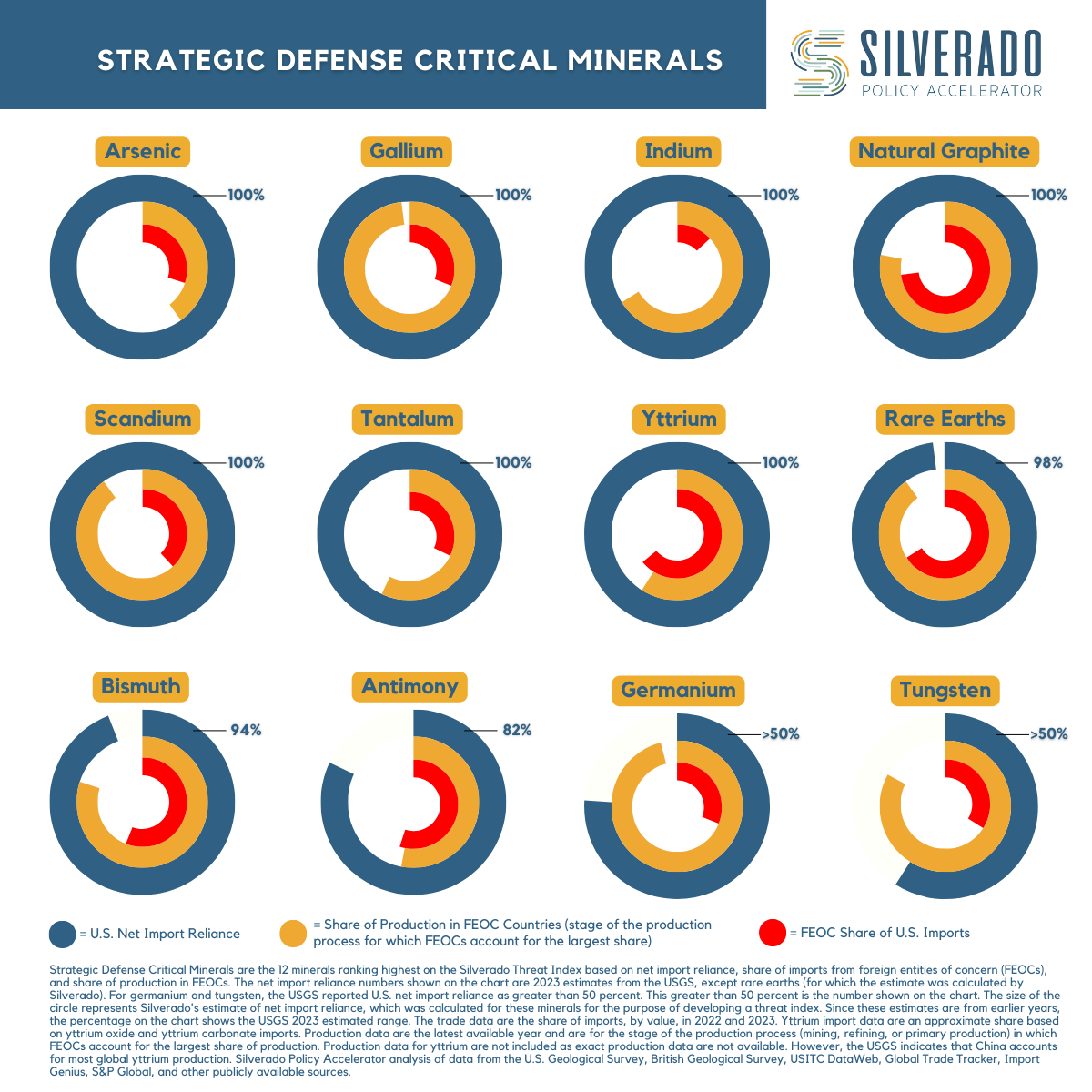

Recognizing that critical minerals are vital across various industries, from electric vehicles to advanced technology and defense systems, Silverado Policy Accelerator (Silverado) used a geopolitical and national security lens to further parse the U.S. government’s critical minerals lists to drive action where there is the most acute need. What emerged is a "strategic defense critical minerals" grouping, which identifies 12 minerals that pose the greatest risk to U.S. national security. The 12 strategic defense critical minerals include antimony, arsenic, bismuth, gallium, germanium, indium, natural graphite, rare earth elements, scandium, tantalum, tungsten, and yttrium.

These minerals are essential to defense applications, with the U.S. dangerously dependent on FEOCs for supply of both the raw and processed form of the mineral. Strategic defense critical minerals are not just vital for defense technologies such as missile systems, military aircraft, and ammunition, but most of these minerals also form the backbone of semiconductor production, which powers key sectors from communications to energy. Shockingly, the U.S. is either fully or almost fully reliant on imports for 9 of these 12 strategic defense minerals, creating a critical vulnerability that could disrupt key industries if the supply is restricted or even suddenly cut off due to a variety of reasons, including government measures such as export controls or bans imposed for geopolitical or national interest reasons.

Graphic produced by Shailyn Lineberry

To pinpoint which critical minerals demand policymakers’ immediate attention, Silverado refined the U.S. government’s broader list of critical minerals by creating a data-driven threat index, isolating those most crucial for national security and classifying them as "strategic defense critical minerals.”[i] First, Silverado referenced the Department of Defense's Strategic Materials of Interest List, which defines these materials as those essential to military and key civilian industries, but not sufficiently available or produced domestically to meet U.S. needs. Silverado then cross-referenced this list with the USGS Critical Minerals List (latest version is 2022) retaining critical minerals present on both lists, narrowing the selection to 32 critical minerals.[ii]. Next, Silverado developed a weighted threat index for each of the 32 minerals based on three factors: (1) U.S. net import reliance; (2) the share of imports from China and Russia; and (3) China and Russia’s share of global production (based on the stage of the value chain where China and Russia account for the largest share of production).[iii] The share of imports was the average for 2022 and 2023, while other data were 2023 or the most recent available year. Each of the three factors was weighted and the 12 critical minerals with the highest “threat index” scores were defined as “strategic defense critical minerals.”

Silverado’s strategic defense critical minerals grouping equips policymakers with information to take swift, proactive measures to secure critical supply chains, reduce FEOC dependencies, and safeguard national defense capabilities. Using a risk-based and evidence-based approach to marshalling government resources and policy action is the most prudent path to ensuring U.S. economic and national security remain resilient and protected. This approach also can provide a blueprint for additional efforts for action on a range of other critical minerals used to support the clean energy transition and other applications.

[i] It is notable that a number of the strategic defense critical minerals are also necessary for clean energy applications.

[ii] The count of 32 minerals is based on grouping rare earths, other than scandium and yttrium, together.

[iii] The data were compiled from the U.S. Geological Survey, British Geological Survey, USITC DataWeb, Global Trade Tracker, S&P Global, and other publicly available sources.

The authors would like to thank Paige Graham for her contributions to the analysis.